The Unavoidable March East: Refuting Darryl Cooper’s Revisionism

How Antisemitism, Expansionism, and the Pursuit of Perpetual War Made Hitler’s Invasion of the Soviet Union Inevitable

Thesis vs Antithesis

Hegel’s dialectical method provides a useful framework for understanding the development of ideas. According to this model, intellectual progress begins with a Thesis—an established viewpoint or prevailing idea. An Antithesis, a counterpoint that introduces contradiction then challenges the Thesis. The resulting tension between the two produces a Synthesis, which brings about a new understanding. This process requires careful engagement with the Thesis to ensure the intellectual rigor of the Antithesis. Only then can intellectual growth occur through the formation of a well-grounded Synthesis.

My critique of Darryl Cooper centers on his refusal to perform his duty as the Antithesis, which undermines the dialectical process detailed above. Like him, I am an amateur researcher without formal credentials. However, I approach my military research by rigorously building upon the established Thesis in my field of study, the foundational knowledge that must be critically engaged with when developing new ideas.

When I introduce an Antithesis—an argument that challenges the prevailing Thesis—I recognize my responsibility to engage with the Thesis directly. This engagement is not optional; all honest historians posses an epistemological obligation to address the existing evidence and reasoning that support the Thesis. Eschewing this responsibility renders the Antithesis intellectually dishonest.

Avoiding Scrutiny Through Audio

I expected to see Darryl Cooper, America’s “best and most honest historian”, challenge the prevailing Thesis and provide evidence for his Antithesis. However, Darryl avoids this responsibility by rejecting the historical community’s standard medium, meticulously documented and easily reviewable text, as his primary mode of communication. Instead, he opts for audio—a clever, yet evasive, strategy to advance his Antithesis.

A credible historian presenting an Antithesis must engage with the Thesis and substantiate their claims using rigorously referenced and accessible documentation. With thoroughly sourced text, especially in digital formats, the historical community can efficiently scrutinize Cooper’s evidence and provide meaningful critiques. By relying on audio, he forces others to painstakingly track down his sources, effectively shielding himself from the rigorous critique his arguments might otherwise face.

I can attest that the delay in completing this article stems from the additional effort required to investigate his audio content instead of consulting the historical community’s preferred medium—comprehensive, source-supported text. This added layer of friction discourages thorough review, ensuring fewer scholars will engage critically with his work. Consequently, Cooper’s approach leaves his audience with fewer meaningful critiques to consider, diminishing the overall value of the discourse.

To begin my critique, I will fairly summarize Cooper’s Antithesis: “If Churchill had negotiated with Hitler after his successful invasions of Poland and France, then World War II could have been avoided.” This reasoning only holds if one believes that Hitler lacked ideological reasons conquest. Therefore, we must now ask the following question.

Was Hitler’s Eastern Invasion Inevitable?

To accept Cooper’s Antithesis, one must believe that Hitler's eastern invasion wasn't inevitable. This position, drawn from his latest podcast, stands as his definitive take on the subject, for now.

The second objection is that Hitler had always had his eyes set on the east, and would have eventually invaded regardless of what the Allies did. And that may be true. Jim Jones and the hostage-taking father may have killed their families no matter how much they were appeased. But maybe not. And, agree or disagree, that “maybe” is worthy of discussion.

This “discussion” has been settled for several decades. Yet Cooper, whether out of ignorance or malevolence, refuses to acknowledge that his position lost, leading to the current Thesis: that Hitler’s invasion was inevitable. If Cooper wishes to reopen this debate, he holds the epistemological responsibility to present compelling evidence that directly refutes the established Thesis.

I cannot find any example of Cooper attempting to refute the current Thesis (using meticulously documented and easily reviewable text would make it easier for me to find it). I searched for the evidence Cooper presented in his previous work to back his Antithesis, but all I found were X posts stating that Hitler sincerely wanted peace (Of course, “peace” in Hitler’s terms simply meant his victims surrendering without resistance).

We can be skeptical of Hitler’s motives for offering peace again and again, and for holding back against British civilians despite months and months provocations, but the fact is that Germany was offering peace, and by all accounts sincerely wanted it

Three Reasons that Hitler’s Invasion was Inevitable

Having established the lack of substantive evidence supporting Cooper's Antithesis, let us now examine his broader claim: that Hitler might not have invaded the East if the UK had surrendered. To counter this argument, I will present three compelling reasons to demonstrate why Hitler’s invasion was, in fact, inevitable.

Antisemitism

Darryl argued on Tucker Carlson’s podcast that Hitler's views on Stalin became complicated when he began to see the U.S. as the primary threat and noticed the Soviet Union shifting away from its commitment to international communism. If true, this would provide much stronger evidence that Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union was not inevitable. Unfortunately for Cooper, I am unaware of a single shred of evidence to validate his claim.

There’s this idea that the only reason that they did Molotov Ribbentrop was because Hitler needed to buy time so he could eventually invade the Soviet Union later or something like that. Not exactly true. I mean, obviously, he was talking about the eventual conflict with the Soviet Union very early in his career that was there. But by the time you get up to 1939, his views are starting to become more complicated on it, where he’s starting to see the United States as the real chief threat, not just to Germany, but to Europe, because he saw himself as the sort of European defender, Messiah guy, right? And he looks over at Joseph Stalin and says, and a lot of his people kind of thought this way, that this is not an international communist movement anymore.

The fact that Cooper feels comfortable pushing such a radical claim without refuting the Thesis or providing evidence for his assertion highlights his dishonesty and lack of credibility. Unfortunately, I have friends who find Cooper credible so I will model credibility by providing the evidence that contradicts Cooper’s Antithesis.

Here is Hitler’s speech to the Reichstag on June 22, 1941, announcing the invasion of the Soviet Union. In this speech, Hitler refers to the Soviet Union as a “Jewish Bolshevik” regime—a phrase he consistently used for decades. If Hitler’s views on the Soviet Union become complicated, then Cooper holds the epistemological responsibility to prove it.

For more than two decades the Jewish Bolshevik regime in Moscow had tried to set fire not merely to Germany but to all of Europe ... The Jewish Bolshevik rulers in Moscow have unswervingly undertaken to force their domination upon us and the other European nations and that is not merely spiritually, but also in terms of military power ... Now the time has come to confront the plot of the Anglo-Saxon Jewish war-mongers and the equally Jewish rulers of the Bolshevik Centre in Moscow!

Hitler’s antisemitism, which Cooper deliberately downplays, fueled his Nazi ideology. Maybe if Cooper used proper research methods, he would have stumbled on Hannah Arendt’s amazing insight that the Nazis BELEIVED the fabricated Protocols of the Elders of Zion. They wanted to replace, “Anglo-Saxon Jewish war-mongers and the equally Jewish rulers of the Bolshevik Centre in Moscow“ with German domination.

In another curious and roundabout way, however, the Nazis gave a propaganda answer to the question of what their future role would be, and that was in their use of the "Protocols of the Elders of Zion" as a model for the future organization of the German masses for "world empire."

Nevertheless, this forgery was mainly used for the purpose of denouncing the Jews and arousing the mob to the dangers of Jewish domination. In terms of mere propaganda, the discovery of the Nazis was that the masses were not so frightened by Jewish world rule as they were interested in how it could be done

Cooper refused to attack the mountain of evidence that supports the current Thesis and only presented one piece of unsubstantiated “evidence” to support his Antithesis. Cooper claimed that “[Hitler] looks over at Joseph Stalin and says that this is not an international communist movement anymore”, but Hitler believed, wrote, and spoke for decades about how he needed to defeat the “Jewish Bolshevik regime in Moscow.” This pivotal aspect of Hitler’s worldview stems from his fervent belief in the fabricated Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which claimed that the “Anglo-Saxon Jewish war-mongers and the equally Jewish rulers of the Bolshevik Centre in Moscow” secretly controlled the world.

Expansionism

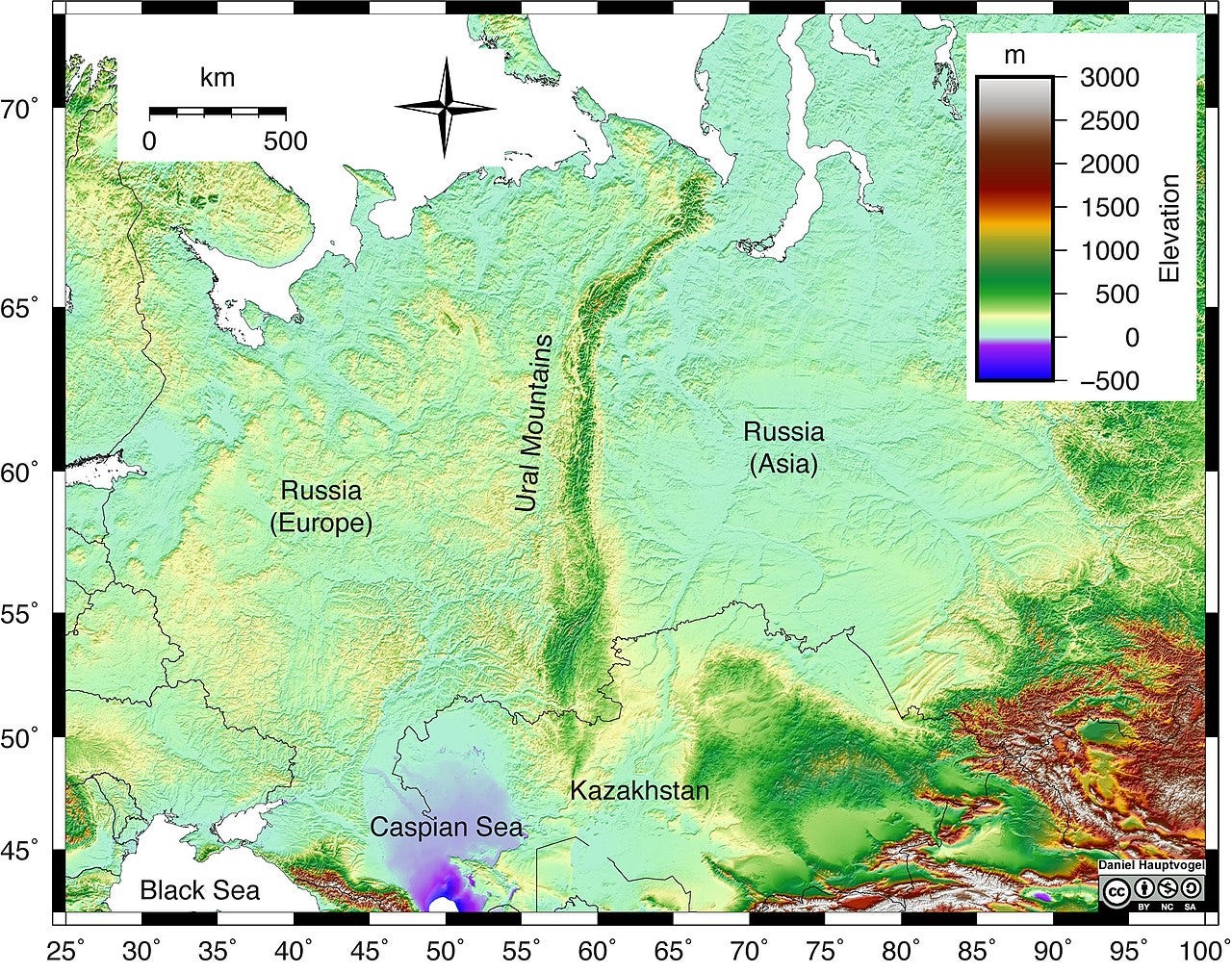

Hitler was driven not only by a pathological hatred of Jews but also by ambitions for conquest reminiscent of Genghis Khan. Like Russia, Germany finds itself in the heart of the largely borderless European Plains—a region that offers few natural defenses. A glance at a map reveals the most logical boundaries for a Nazi empire: to the west, the Atlantic Ocean provides a secure border, while to the southwest, the Pyrenees, Alps, and Carpathian Mountains offer natural protection from southern neighbors.

Continuing eastward, the Caspian Sea, Caucasus Mountains, and Black Sea would shield a Nazi empire from threats originating in West Asia. To the northeast, the Ural Mountains would serve as a natural barrier against Asiatic forces, leaving only a small, vulnerable—yet defensible—pocket in the Central Asian steppes.

Looking at a map of the Nazi empire, we can see that they traced the western borders I outlined and were pushing towards the northeastern border denoted by the Ural Mountains.

I assumed that if the UK made peace with Hitler then Hitler was going to push East eventually until he reaches the Ural Mountains. But unfortunately, I was wrong. On September 23rd, 1941 (two months after he began his invasion of the Soviet Union) Hitler claims that the Ural Mountains provides just as much protection as a river.

It's absurd to try to suppose that the frontier between the two separate worlds of Europe and Asia is marked by a chain of not very high mountains—and the long chain of the Urals is no more than that. One might just as well decree that the frontier is marked by one of the great Russian rivers. No, geographically Asia penetrates into Europe without any sharp break.

How can Hitler claim that a 2,500 kilometer mountain range featuring an average elevation of 1,000 meters provides just as much protection as a river? If the Urals does not satisfy Hitler, then no border would satiate Hitler’s desire for conquest.

The Pursuit of Perpetual War

Antisemitism and expansionism made peace with Hitler unlikely, but his obsession with war rendered it impossible. Typically, leaders wage war to achieve specific political goals, allowing for negotiation over those objectives. But what happens when war itself becomes the goal? Hitler demonstrated his goal of perpetual warfare in his remarks from August 19, 1941, as recorded in Hitler’s Table Talks.

For the good of the German people, we must wish for a war every fifteen or twenty years. An army whose sole purpose is to preserve peace leads only to playing at soldiers—compare Sweden and Switzerland. Or else it constitutes a revolutionary danger to its own country.

Hitler’s statement reveals his belief that war serves as an end in itself—a necessary and recurring process to maintain the vitality and discipline of the German people. He dismissed the idea of a military focused solely on preserving peace, arguing that such armies, like those of neutral nations such as Sweden and Switzerland, become ineffective and ceremonial. Moreover, Hitler warned that an idle military without an external enemy could turn inward, posing a revolutionary threat to its own nation. Hitler's commitment to perpetual conflict rendered negotiation, he desired war for war’s sake.

Conclusion

Darryl Cooper’s Antithesis fails to meet the intellectual rigor required to challenge the prevailing Thesis that Hitler’s invasion of the East was inevitable. The overwhelming evidence—including Hitler’s deep-rooted antisemitism, his boundless territorial ambitions, and his ideological commitment to perpetual war—makes clear that negotiation or appeasement would not have altered his course. By failing to engage meaningfully with the established Thesis, Cooper not only undermines his own credibility but also does a disservice to the dialectical process, offering a distorted narrative instead of contributing to intellectual progress.